Summary: Radial Mountain Bike Tires

The mountain bike industry stands at a precipice of a fundamental technological shift, moving from the century-old bias-ply tire construction method to radial casing technology. This transition, while standard in the automotive and motorcycle industries for decades, represents a radical departure for bicycle dynamics, challenging long-held assumptions regarding tire pressure, sidewall stability, and the interplay between grip and rolling efficiency. Spearheaded by Schwalbe with the introduction of the Albert and Magic Mary Radial tires, and rapidly followed by emerging competitors like Zleen, this technology promises a transformative improvement in traction, damping, and control.

This comprehensive report provides an in-depth technical analysis of radial tire technology within the context of mountain biking. It explores the structural physics distinguishing radial from bias-ply casings, evaluates the specific engineering achievements of Schwalbe’s new lineup, and assesses the performance implications for trail speed, contact patch dynamics (“footprint”), and rider safety. Furthermore, it analyzes the market trajectory for 2026, considering whether this innovation will become the new industry standard or remain a specialized niche. Through a synthesis of laboratory data, professional racing results, and rheological theory, this document serves as a definitive resource on the current state and future of radial mountain bike tires.

See the latest prices on Schwalbe Radial Mountain Bike Tires here –> Schwalble Radial Tires

1. Introduction: The Stagnation and Evolution of the Pneumatic Interface

For over a century, the bicycle tire has relied on a construction method that predates the invention of the mountain bike itself: the bias-ply casing. While frame materials have evolved from steel to hydroformed aluminum and high-modulus carbon fiber, and suspension systems have advanced from simple elastomers to sophisticated hydraulic circuits with independent high- and low-speed damping, the tire—the sole point of contact with the ground—has remained structurally conservative.

1.1 The Bias-Ply Legacy

The bias-ply, or cross-ply, tire is defined by its internal architecture. Layers of rubberized fabric, typically nylon in modern cycling applications, are laid diagonally across the tire carcass from bead to bead. These plies are arranged at alternating angles, typically around 45 degrees relative to the direction of travel. When the tire is cured, these overlapping layers form a rigid, crisscross lattice structure.

This design has persisted for good reason. The opposing tension of the crossed fibers creates a mechanically stable structure. The sidewalls are inherently stiff because the fibers brace against one another, providing substantial resistance to lateral deflection. In the context of a two-wheeled vehicle that steers via leaning (camber thrust), this lateral stiffness is crucial for maintaining a predictable trajectory. A tire that collapses under side loads leads to vague handling, rim strikes, and potentially catastrophic “burping” of air in tubeless systems.

However, this structural rigidity comes with a parasitic cost: hysteresis. As the tire rolls and encounters obstacles, the casing deflects. In a bias-ply tire, the crossing fibers must shear against one another—a phenomenon often described as the “scissor effect”. This internal friction generates heat and, more importantly, dissipates energy that could otherwise be used to propel the bicycle forward. Furthermore, this interlocked structure couples the sidewall to the tread cap. When the sidewall is compressed by a bump, it pulls on the tread, potentially distorting the contact patch and reducing the tire’s ability to conform to the terrain.

1.2 The Radial Promise

Radial tire technology, introduced to the automotive world by Michelin in the late 1940s, revolutionized vehicle dynamics by decoupling the sidewall from the tread. In a true radial tire, the casing cords run perpendicularly to the direction of travel—at 90 degrees to the bead—taking the shortest path across the tire. This arrangement eliminates the scissoring action of the cross-plies.

The theoretical benefits for mountain biking are profound. A radial casing is structurally supple in the vertical plane, allowing the sidewall to bulge and absorb impacts without pulling the tread away from the trail surface. This decoupling means the tread can remain flat and planted, maximizing the contact patch. The reduction in internal friction suggests a potential for lower rolling resistance, while the increased compliance offers a form of pneumatic suspension that could rival the small-bump sensitivity of the bike’s fork and shock.

1.3 Historical Failures and Modern Resurrection

Attempts to bring radial tires to bicycles are not new. Maxxis, for example, introduced the “Radiale” road tire years ago.However, these early iterations often struggled with the unique physics of bicycles. Unlike cars, which corner primarily through slip angles on four wheels, bicycles lean. A tire with extremely soft sidewalls can feel unstable or “floppy” when leaned over, leading to a sensation of the tire rolling underneath the rim.

The breakthrough in 2024 and 2025, led by Schwalbe, was the realization that a “pure” 90-degree radial construction might be too extreme for the high-lean, low-pressure environment of mountain biking without the heavy steel belts used in cars. The solution was a hybrid approach: a radial-style construction that utilizes a very obtuse thread angle—significantly steeper than the traditional 45 degrees but not quite a vertical 90 degrees. This engineering compromise retains sufficient lateral stability while unlocking the compliance and grip benefits of the radial architecture.

2. The Physics of Radial Construction: A Deep Dive

To understand why the Schwalbe Albert and Magic Mary Radial tires behave differently on the trail, one must analyze the vector forces at play within the casing. The shift from an acute (bias) to an obtuse (radial) thread angle fundamentally alters the spring rate and damping coefficient of the pneumatic system.

2.1 Casing Geometry and Deformation Mechanics

The structural behavior of a tire casing can be modeled as a composite pressure vessel. In a bias-ply tire, the tension is distributed across the diagonal matrix. When a localized impact occurs—such as a sharp rock edge—the force is transmitted broadly across the casing due to the interlocked nature of the fibers. The entire structure resists deformation, resulting in a stiffer, springier feel.

In Schwalbe’s radial design, the threads are arranged at a much blunter angle. This effectively shortens the path of the fibers from bead to bead, reducing the amount of material required to span the gap and changing the tension vectors.

- Linear Deformation: The radial casing exhibits a more linear spring curve compared to the progressive ramp-up of a bias-ply tire. This means that for a given unit of force input (a bump), the tire deflects more readily and predictably.

- Independent Sidewall Action: Because the fibers are not locked in a diagonal shear pattern, the sidewall can flex largely independently of the crown (tread area). When the tire compresses, the sidewall bulges outward without dragging the shoulder knobs inward or lifting the center tread. This mechanical isolation is the key to the “footprint” expansion that defines radial performance.

2.2 The “Footprint” Phenomenon: Contact Patch Dynamics

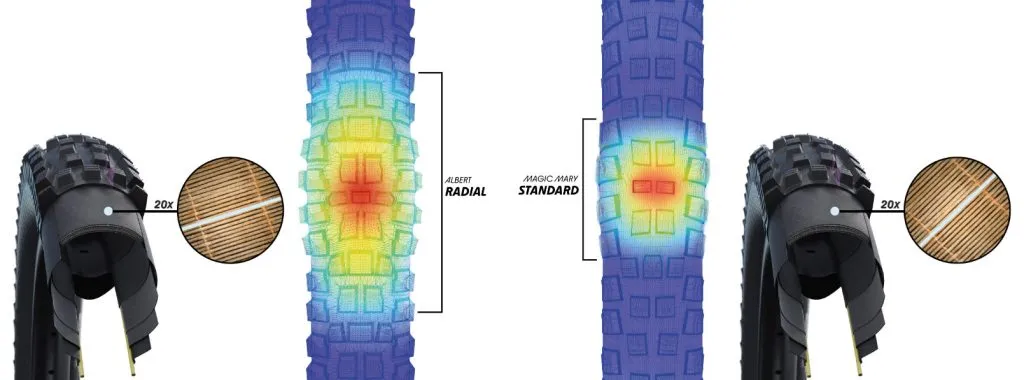

The most touted metric of the new radial generation is the increase in contact patch size. Schwalbe claims a 30% larger contact patch at equivalent pressures compared to standard tires.

- Elongation vs. Widening: In a bias-ply tire, lowering pressure typically elongates the contact patch longitudinally. In a radial tire, the patch expands significantly in both width and length because the casing does not resist the flattening deformation as aggressively.

- Pressure-Independent Grip: This is a critical distinction. Usually, gaining a 30% larger contact patch would require dropping tire pressure by 5-8 psi, entering a danger zone for rim strikes and tire squirm. Radial technology achieves this contact area without lowering pressure. In fact, tests show that a radial tire at 28 psi maintains a 10% larger contact patch than a bias-ply tire at 22 psi. This allows the rider to run higher pressures—protecting the rim and stabilizing the sidewall—while enjoying the traction benefits of a soft, conforming tire.

2.3 Hysteresis and Damping (The “Thud” Factor)

Hysteresis refers to the energy lost as heat when a material deforms and then returns to its original shape. In suspension tuning, this energy loss is desirable; it is called damping. A spring without damping oscillates uncontrollably.

- Bias-Ply Damping: Bias-ply tires have high internal friction due to the rubbing of crossed plies. While this provides some damping, the structural stiffness often overcomes it, leading to a “pingy” or undamped rebound feeling on sharp impacts. The tire acts like a stiff spring that deflects off obstacles rather than absorbing them.

- Radial Damping: The radial construction reduces the inter-ply friction, which might theoretically suggest lessdamping. However, because the casing is so supple, it allows the tire to utilize the air spring more effectively and minimizes the high-frequency vibration transmission to the rider. The result is a sensation often described as a “thud”. When the tire hits a square-edge hit, it absorbs the energy without the violent elastic return seen in bias-ply tires. The tire stays glued to the ground rather than skipping, which is critical for maintaining braking traction and cornering lines on chattery terrain.

2.4 Zleen’s “True Radial” Counter-Argument

While Schwalbe uses an obtuse angle (likely 75-80 degrees), the Czech manufacturer Zleen has entered the market with the “Racerunner Radical,” boasting an 88-degree casing angle. Zleen argues that their design is the “first true radial” bicycle tire.

- The 88-Degree Angle: By pushing the angle to nearly 90 degrees, Zleen maximizes the suppleness and rolling resistance benefits. They claim a 40% reduction in rolling resistance and a 25% weight reduction.

- Engineering Challenges: A near-90-degree angle provides almost zero lateral stability on its own. Zleen likely relies on a very specific bead construction and potentially a stiffer tread cap or cap-ply to prevent the tire from feeling unstable. This highlights the engineering trade-off: Schwalbe compromised on the angle to ensure stability for gravity riding, while Zleen pushed the angle to the limit for XC efficiency.

2.5 Thermodynamics: Hysteresis and Heat Dissipation

One often overlooked advantage of radial construction is its thermal efficiency. In motorsports, radial tires are prized not just for grip, but for their ability to manage heat buildup.

- Reduced Friction: In a bias-ply tire, the “scissoring” of the crisscrossed layers generates significant internal friction (hysteresis) as the tire deflects. This friction converts kinetic energy into heat. On a long, rough alpine descent, or under the heavy load of an eMTB, a bias-ply casing can build up substantial heat.

- Compound Stability: Excessive heat can alter the properties of the rubber compound, causing the damping characteristics to fade or the knobs to become squirmy. The radial design, with its parallel ply orientation, significantly reduces this internal friction. This ensures that the tire’s performance remains consistent from the top of the run to the bottom.

- Energy Efficiency: For eMTBs, this reduced hysteresis translates directly to battery range. Less energy wasted as heat in the casing means more energy available for propulsion. This thermodynamic efficiency, combined with the ability to maintain traction under high torque, reinforces the radial tire as the superior choice for electric mountain bikes.

2.6 The Bead-Rim Interface: A New Load Paradigm

The shift to radial casings fundamentally changes how forces are transmitted to the rim, creating new engineering challenges for bead retention.

- Force Vectors: In a bias-ply tire, the diagonal arrangement of the cords creates a “constricting” effect that naturally tightens the bead against the rim under load. Radial tires, however, lack this diagonal bracing. The internal air pressure exerts a more direct radial expansion force, pushing the bead outward and upward away from the rim bed.

- Bead Stiffness Requirement: To counteract this, radial tires require a bead core with exceptionally high tensile strength and zero stretch. If the bead core stretches even microscopically, the tire can blow off the rim. This is why Schwalbe explicitly mandates strict adherence to pressure limits and rim compatibility standards.

- Hookless Rim Implications: This has significant implications for hookless (straight-side) rims. Hookless rims rely entirely on the tire bead’s tensile strength and exact diameter tolerance to prevent blowouts. The increased radial expansion forces of a radial casing reduce the safety margin on hookless systems. Riders using hookless rims must be hyper-vigilant about tire pressure, as the mechanical lock provided by a rim hook is absent to backup the bead’s tension. Schwalbe’s “high-strength bead core” is a direct engineering response to this increased stress.

3. Schwalbe’s Radial Ecosystem: Technical Breakdown

Schwalbe did not merely release a single “radial” model; they restructured their high-performance gravity lineup around the technology. This strategy centers on the all-new Albert and the updated Magic Mary Radial.

See the latest prices on Schwalbe Radial Mountain Bike Tires here –> Schwalble Radial Tires

3.1 The Albert Radial: Designed for the Casing

The Albert is the first tire in Schwalbe’s lineup designed from the ground up specifically for radial construction. Its design philosophy diverges sharply from traditional logic.

- Rounded Profile: Most gravity tires (like the Magic Mary or Maxxis Assegai) feature a square profile with pronounced shoulder lugs to “rail” corners. The Albert, however, has a visibly rounder profile.

- Dense Knob Spacing: The tread features more tightly spaced knobs compared to the Magic Mary. In a rigid bias-ply tire, this might reduce grip in loose soil because the knobs wouldn’t penetrate deep enough. However, the radial casing allows the tire to flatten so significantly that the sheer quantity of rubber on the ground compensates for the lack of mechanical keying depth.

- Intended Application: The Albert is positioned as the ultimate all-rounder. It excels in dry, loose-over-hard, and hardpack conditions where surface area contact is king. The radial casing allows it to conform to micro-terrain (roots, rock faces) that a stiffer tire would skate over.

3.2 The Magic Mary Radial: Enhancing a Classic

The Magic Mary is perhaps the most celebrated intermediate/soft-condition tire in modern mountain biking. Schwalbe’s decision to apply radial technology to this existing tread pattern serves as a perfect A/B test for the technology.

- Tread Continuity: The tread pattern remains identical to the bias-ply version: widely spaced, aggressive square lugs.

- Performance Evolution: On a bias-ply casing, the Magic Mary is known for its bite in soft soil but can feel squirmy or slow on hardpack. The radial version transforms this character. The improved casing stability (when run at appropriate pressures) allows the tall knobs to track better on hard surfaces without folding, while the increased compliance allows the tire to find grip on wet roots and off-camber sections where the bias-ply version might deflect.

- The “Dirty Dan” Secret: It is now known that the radial Magic Mary (and Albert) prototypes were raced under the “Dirty Dan” label for several seasons. Amaury Pierron’s devastatingly fast runs at the Les Gets World Cup—a track infamous for slippery, grease-like mud—were won on these radial tires. The ability to run high pressures (30+ psi) to prevent rim strikes while maintaining the suppleness needed for traction was the decisive advantage.

3.3 The Shredda: Extreme Specificity

The Shredda represents the radial concept taken to its logical extreme for e-mobility.

- Moto Influence: Visually resembling a motocross tire, the Shredda features a massive tread depth that would be unsupported on a standard bicycle casing.

- Radial Support: The radial casing provides the necessary base to support these massive lugs without the tire collapsing under the heavy torque and weight of an eMTB. This tire is designed as a “loamer cheat code,” specifically for deep, soft terrain where maximum mechanical interlocking is required.

3.4 Compound Synergy: Addix Soft vs. Ultra Soft

The radial casing’s performance is inextricably linked to Schwalbe’s Addix rubber compounds.

- Addix Ultra Soft (Purple): This compound is essential for the front tire in gravity applications. The extreme damping of the Ultra Soft rubber pairs with the casing’s compliance to create a “dead” feel that eliminates trail chatter.

- Addix Soft (Orange): The Albert is often specced with Addix Soft in the rear or for trail use. The radial casing helps mitigate the slightly lower grip of the harder compound by maximizing the contact patch, effectively giving “Ultra Soft” levels of grip with “Soft” levels of durability and rolling speed.

4. Performance Analysis: The Rider Experience

Integrating data from professional reviews and rider feedback reveals a consistent narrative regarding the performance of radial tires. The transition requires a recalibration of rider expectations and setup habits.

4.1 The “Footprint” Effect in Action

The claim of a larger contact patch is not just marketing hyperbole; it is the central functional attribute of the tire.

- Climbing Traction: Riders report a significant improvement in technical climbing traction. On steep, rooty, or loose ascents, the radial tire conforms to the terrain rather than spinning out. This is particularly noticeable on eMTBs, where the motor’s torque often breaks traction on bias-ply tires.

- Cornering Consistency: The Albert, in particular, is praised for its consistency. Unlike some tires that have a distinct “drift zone” between the center and side knobs, the radial casing allows for a smooth transition. The tire feels planted throughout the lean angle, reducing the “on/off” grip sensation.

- Braking: The expanded contact patch significantly improves braking authority. The tire can transmit more deceleration force to the ground before locking up, allowing for later braking into corners.

4.2 Damping and Ride Quality

The acoustic and tactile feedback of radial tires is distinct.

- The “Thud”: Riders consistently describe the sound of the tire as a “thud” rather than a “ping”. This auditory cue reflects the tire’s ability to dissipate energy.

- Vibration Reduction: The tire acts as a low-pass filter for trail noise. High-frequency vibrations (chatter, washboard) are absorbed by the casing before they reach the suspension or the rider’s hands. This leads to reduced fatigue on long descents.

4.3 Rolling Resistance: The Nuance

Rolling resistance is often misunderstood. On a smooth drum in a lab, a sticky, soft tire with a massive contact patch (like the radial Magic Mary) might test poorly due to high adhesive friction and hysteresis.

- Impedance Matching: However, off-road rolling resistance is largely determined by “impedance”—the energy lost when the bike is forced to move up and over obstacles. Because radial tires absorb these obstacles, the bike maintains forward momentum. Therefore, while they may feel slower on asphalt, they are often faster on rough trail segments.

- Zleen’s Efficiency Claims: Zleen explicitly targets the rolling resistance metric, claiming their 88-degree casing reduces resistance by 40%. This suggests that for XC applications, where speeds are higher and terrain is smoother, the pure radial design (with less hysteresis from scissoring plies) offers a massive efficiency advantage.

4.4 The Pressure Sensitivity “Goldilocks” Zone

The most critical operational difference is pressure sensitivity.

- The +5 PSI Rule: Riders cannot run their standard bias-ply pressures. A radial tire at 22 psi will feel wallowy and unsupported in corners, leading to rim strikes.

- The New Normal: The consensus recommendation is to increase pressure by approximately 2-5 psi. For a typical enduro rider, this might mean moving from 23 psi to 27 or 28 psi.

- The Tight Window: The operating window is narrow. A deviation of just 2 psi can ruin the ride feel—too low and it squirms; too high and it loses its damping magic and becomes bouncy. Digital gauges are essential tools for radial tire owners.

4.5 Durability Nuance: Cut Resistance vs. Perceived Fragility

Rider feedback often highlights a contradiction: the tires feel thin and “flimsy” to the touch, yet they survive hardcore use. This paradox is explained by the mechanics of cut resistance relative to fiber orientation.

- Vertical vs. Lateral Strength: In a bias-ply tire, the crisscrossed layers create a “fence” that is generally resistant to cuts from all angles. In a radial tire, the fibers run parallel from bead to bead. While the tire is robust against impacts that compress it vertically (pinch flats), the sidewall is theoretically more vulnerable to sharp objects slicing between the parallel fibers.

- The Gravity Pro Solution: To mitigate this vulnerability, Schwalbe’s Gravity Pro radial casing includes specific reinforcements to protect the sidewall. This explains why trail riders on the lighter “Trail Pro” casing might report mixed durability in jagged rock gardens—a slice parallel to the radial cords can propagate more easily than in a cross-ply weave. Riders in sharp, rocky terrain are strongly advised to opt for the Gravity Pro casing despite the weight penalty.

4.6 System Integration: The Suspension Dependency

Adopting radial tires is not just a rubber upgrade; it is a suspension modification.

- Tire as First-Stage Suspension: The tire acts as an undamped air spring that handles high-frequency chatter (10-50Hz) that suspension forks cannot react to due to seal friction (stiction). Because radial tires are significantly more compliant in this frequency range, they effectively add low-speed compression compliance to the bike.

- Rebound Tuning: The most common setup error is failing to adjust the fork and shock rebound. Because the tire absorbs more energy and rebounds less violently (the “thud”), the bike’s suspension can often be run with slightly faster rebound settings to maintain liveliness. Conversely, the increased compliance can mask a poor suspension setup, making a harsh fork feel acceptable—until the rider hits a hit big enough to bottom out the tire and overwhelm the suspension. Riders should re-bracket their suspension settings after installing radial tires.

5. Market Analysis and Future Outlook: 2026 and Beyond

As the industry moves into the 2026 model year, the question remains: Is radial technology a permanent evolution or a passing trend? The evidence points strongly toward permanence, driven by competitive pressure and the specific needs of modern mountain bikes.

5.1 The Competitive Landscape

Schwalbe’s first-mover advantage has spurred a reaction from major competitors.

- Zleen: This Czech brand is positioning itself as the “purist” radial option. Their focus on the XC/Marathon market with the Racerunner Radical fills a gap Schwalbe has largely ignored (gravity focus). Zleen’s ability to deliver a 550g radial tire proves the technology is not inherently heavy, potentially opening the floodgates for weight weenies.

- Maxxis: The market leader is undoubtedly developing a response. Rumors of “Test Pilot” tires with novel casing constructions have been circulating. Maxxis has a history of adopting successful technologies (e.g., DoubleDown casing) and refining them. It is highly probable that a “Maxxis Radial” or similarly named technology will debut in 2026, possibly leveraging their existing Silkworm or SilkShield technologies in a new layout.

- Continental: Having recently overhauled their gravity range to great acclaim , Continental is unlikely to rest. Their expertise in automotive and motorcycle radials gives them the technical know-how to pivot quickly. We may see a radial iteration of the Kryptotal or Argotal aimed specifically at the eMTB racing circuit.

- Specialized: Rumors suggest Specialized is exploring radial constructions for their Soil Searching tire line. Their close relationship with top-tier factory teams provides a perfect testing ground.

5.2 Stickiness Factors

Several factors ensure radial technology is here to stay:

- The eMTB Catalyst: Electric mountain bikes are heavier and put more torque through the tires. They benefit disproportionately from the durability and grip of radial casings. As eMTBs continue to gain market share, radial tires offer a solution to the “heavy bike” handling penalties.

- Performance Validation: Ten World Cup wins (and counting) by Amaury Pierron and others validates the technology at the highest level. In a sport driven by racing pedigree, this is the ultimate marketing tool.

- Tangible Upgrade: Unlike marginal gains in hub engagement or frame stiffness, the switch to radial tires offers a tangible, immediate improvement in ride quality that average riders can feel. This “thud” sensation is addictive and hard to give up.

5.3 Potential Barriers

- Cost: Radial tires are currently premium products ($100+ USD). High manufacturing complexity keeps prices high.

- Durability Perception: The supple, thin-feeling sidewalls of the Trail Pro casing scare some riders who associate stiffness with durability. Long-term reliability data will be crucial for widespread adoption.

- Rim Compatibility: While current tires fit current rims, optimal performance might require wider hook flanges or specific bead seat profiles in the future to manage the different load vectors of radial casings.

6. Detailed Technical Comparison and Specifications

Table 1: Schwalbe Radial Tire Specifications Comparison

| Feature | Magic Mary Radial | Albert Radial | Shredda Front | Shredda Rear |

| Intended Use | DH / Enduro / eMTB | Trail / Enduro / All-Round | Extreme Gravity / eMTB | Extreme Gravity / eMTB |

| Terrain | Intermediate, Soft, Mixed | Dry, Hardpack, Loose-Over-Hard | Deep Loam, Mud, Soft | Deep Loam, Soft |

| Profile | Square, Edgy | Round, Continuous | Moto-style, Very Deep | Moto-style, Paddle-like |

| Casings | Gravity Pro, Trail Pro | Gravity Pro, Trail Pro | Gravity Pro | Gravity Pro |

| Compounds | Addix Ultra Soft, Soft | Addix Ultra Soft, Soft | Addix Ultra Soft | Addix Ultra Soft |

| Key Benefit | Grip in loose/wet conditions | Massive contact patch on hard/mixed | “Cheat code” for deep soft soil | Propulsion traction |

Table 2: Radial vs. Bias-Ply Technology Matrix

| Characteristic | Bias-Ply (Traditional) | Schwalbe Radial | Zleen “True” Radial |

| Ply Angle | Acute (~45°) | Obtuse (~75-80°) | Near-Vertical (88°) |

| Structure | Interlocked (Scissors) | Linear (Parallel) | Linear (Parallel) |

| Sidewall Stiffness | High (Self-Supporting) | Low (Needs Air Support) | Very Low (Needs Air Support) |

| Contact Patch | Standard | +30% vs Bias | Claimed +30% |

| Damping Feel | Pingy / Active | Thud / Dead / Planted | Supple / Fast |

| Optimal Pressure | Lower (e.g., 22 psi) | Higher (e.g., 27 psi) | Significantly Higher (+70%) |

| Rolling Resistance | High Hysteresis | Low Impedance | Claimed -40% (Low Hysteresis) |

| Primary Weakness | Deflection / Chatter | Lateral Stability at Low PSI | Lateral Stability / Complexity |

7. Conclusion

The introduction of radial tire technology by Schwalbe, exemplified by the Albert and Magic Mary Radial, marks a pivotal moment in mountain bike engineering. By successfully adapting the physics of radial construction—specifically the decoupling of sidewall and tread—to the unique demands of off-road cycling, Schwalbe has solved the historic compromise between traction and stability.

The data is clear: radial tires allow riders to run higher pressures, protecting their rims and improving lateral stability, while achieving a larger contact patch and superior damping compared to low-pressure bias-ply tires. The “Albert” proves that tread patterns can be redesigned to exploit this new behavior, creating an all-rounder that defies conventional tread logic. Meanwhile, the “Magic Mary Radial” demonstrates that even legendary designs can be elevated by a better casing.

While challenges remain—specifically regarding cost and the learning curve for tire pressure setup—the competitive response from brands like Zleen and the undeniable performance benefits for eMTBs suggest that radial technology will not only stick but likely become the premium standard for performance mountain biking by 2026. For the rider, the radial revolution offers a quieter, grippier, and more controlled ride, provided they are willing to relearn the art of tire pressure.

See the latest prices on Schwalbe Radial Mountain Bike Tires here –> Schwalble Radial Tires